Dear Difference Maker,

We all make a difference. The question is: what kind of difference do we make?

When we see children or adults around us behaving unskillfully or unproductively, with actions that are intended to affront or cause harm, they need our understanding and compassion.

This is the fork in the road, where we find we have a choice of either compassion…or judgment. It’s important to understand that compassion does not mean that you condone hurtful or unskilled behavior. Instead, it’s reaching into yourself to relate to people with a heartfelt energy of compassion that they can hear and assimilate.

Everything that irritates us about others

can lead us to an understanding of ourselves.

– Carl Gustav Jung

Every time I’ve chosen compassion, I find I am deeply astounded, not only at the power of this force, but that it really works to shift and change a situation.

We often miss an essential point. When you go to that compassionate place that’s deep within yourself, to look at the person who is doing something upsetting, you are not only giving compassion, but you are also receiving what you’ve just given.

You simply cannot launch a negative attitude or a judgment at someone and still feel peaceful and good about yourself. During those moments, it’s impossible to feel lovable or safe.

There has been a significant amount of research about compassion, in the areas of human development and behavior.

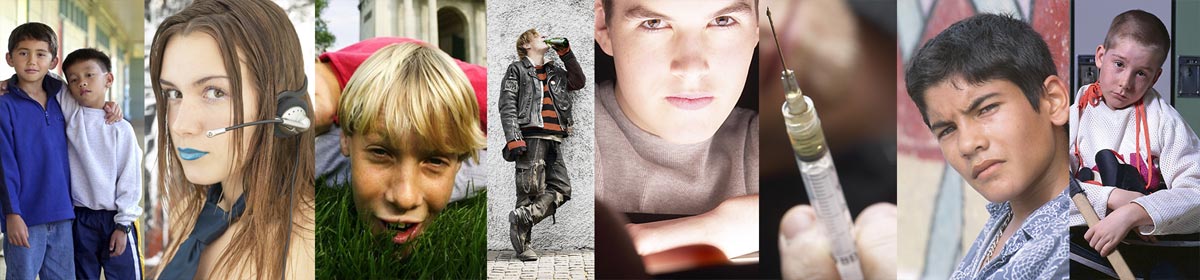

In the most current research-based assessments, psychologists have observed that a compassionate response to challenging individuals and situations yields a positive reaction 70% of the time. Whereas, responding with resentment or anger produces a negative reaction 100% of the time!

As I’ve discussed at length in my Academic Success 101 Online Course, if you want the problematic situations in your life to dissipate and improve, start “throwing compassion” at the person or at the problem behavior. I know it sounds too simple, but try it. The next time you are upset, throw compassion at the problem and see how the situation changes before your very eyes.

Stories like Jamie Lynne’s are small but powerful reminders of what the highest and best part of you already knows: that compassion makes us protective rather than controlling. The difference is crucial in creating long-term, life-enhancing results.

To get what you want, you must give away what you want.

My first experience of putting this principle into practice was when I was thirty-something and had just transferred to a school whose guidance counselor had to take an extended leave. A third-grader named Jamie Lynne was on my individual counseling schedule and her teacher described her as very angry and highly volatile.

Give Away What You Want

Jamie Lynne was pointed out to me in the lunchroom my first day, and what I observed hurt my heart. She was sitting at the end of the table with her little friend Anne, when five other girls approached them. By their demeanor, it was apparent that these five girls considered themselves the elite of the class. They sat down at the table and began taunting Jamie Lynne. Anne tried to stick up for her friend, but the girls continued their harassment.

Jamie Lynne became verbally volatile and the girls made fun of her. A teacher on lunch duty came storming in from across the room and started chastising Jamie Lynne for disruptive behavior and for yelling obscenities at the five “innocent” girls.

I moved in quickly and lightly touched the teacher’s shoulder and asked if it was all right with her if I addressed the taunting behaviors of the five. She stepped back, and I proceeded to let the five girls know that I had seen everything they had said and done to Jamie Lynne. But Jamie Lynne was not able to hear my defense of her.

Since she was so used to taking the fall for other people’s attacks, she didn’t stop to hear that I’d just stood up for her. Instead, she jumped up and ran off with her tray, refusing to stay and hear what I had to say to the other girls.

I did not feel the need to control Jamie Lynne’s behavior at this point. It was painfully obvious that she was on her own when it came to dealing with her classmates. The teacher who had come up to discipline Jamie Lynne quickly saw what was really going on and shifted her attitude.

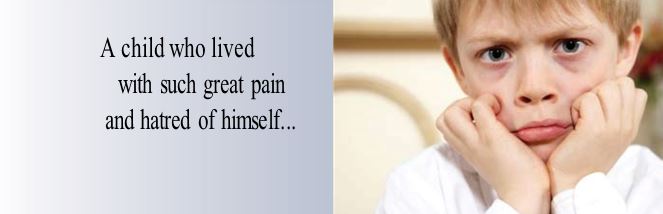

My first meeting regarding Jamie Lynne was with her teacher and mother. Both related only negative accounts about her increasingly volatile behaviors. She had been a sweet and wonderful little girl who suddenly turned angry and hateful in first grade. Nothing happened, of course, that could have caused this turn in her behavior according to the mother. Her conclusion, in her exact words, was that Jamie Lynne was just a “good seed gone bad,” and she was learning to reconcile herself to this fact.

I sat and listened, but elected not to say anything to try to turn their thinking around at this first meeting. I knew, being the new counselor in this school, that I did not have any credibility built up yet, and I needed to have success with Jamie Lynne first.

Later that day, when I met Jamie Lynne coming down the stairs, I said, “Hello Jamie Lynne, I just visited with your mother today, and I’m really looking forward to having you visit with me soon.”

Jamie Lynne took one look at me and screamed, “I hate you! I hate you and I don’t want to come see you. You will never be as good as our real counselor. I hate you. I hate you. Leave me alone; don’t you come near me. I hate you.” And with that, off she went, as angry and as hostile as she could be.

My thoughts assailed me. My first thought was: “Oh my gosh, I hope nobody saw her speak to me that way. My credibility will be destroyed before I’ve even begun.” My second thought: “Wow, how am I ever going to reach this kid?” Then my third thought: “Give away what you want.” My fourth thought asked: “But what do I want?”

And finally, it came to me. My fifth thought was: “I want control.” I went back to my office shaking. I sat there and pondered this most profound experience I realized that first I needed to let go of what someone else might think of a child being so disrespectful of me.

I did that quickly. I knew the name of the game I was in. I was modeling a new way of treating all children, and with any new approach comes adversity and making the most of an opportunity. But where did I go from here?

“Give away what you want. I want control. Now, how do I give that away?”

I sat quietly at my desk, mulling over these thoughts, and then I put myself in Jamie Lynne’s shoes. My gosh, what a painful place for a third grader to live! In her shoes, I realized that the message she’d been getting from the adults in her life was that she was a “bad” girl that needed to be “fixed.”

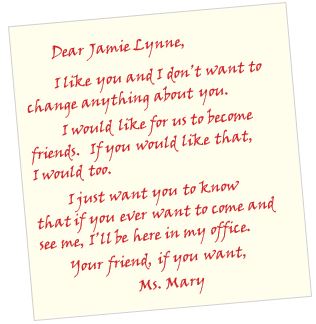

I decided to try a new tactic with Jamie Lynne. I would not position myself as someone who was going to fix her. So with that in mind, I wrote her a note:

As I headed out my door to find Jamie Lynne, she saw me coming and jetted into the girls’ restroom. I followed her in. I looked under the stalls and there were no feet on the floor. She was hiding from me! I reached for the door that I thought she was behind and gently pulled it open. She reacted as if I were going to hit her. I quietly handed her the note then gently closed the door and left.

The next morning, she was at my door with her demands. She would come, but only with her friend Anne, and all they were going to do with me was play games. That was it!

I said, “Deal. When do you want to start coming?”

With each little success, she became eager to learn more.

Jamie Lynne and Anne came once or twice a week. She was initially very resistant and distrustful of any connection with me. Through the board games we all conversations gently unfolded and she connected to me as someone who cared about who she was and how she felt.

Eventually she began trying some “techniques” for dealing with her classmate with each little success she had, she became eager to learn more.

The day I transferred out of the school to another position, she opened her arms to me for the first time, and gave me a big, long hug. I told her how much I loved her and knew she was going to keep doing a great job managing her feelings.

I fought back my own tears as she cried and said good-bye. In giving away the need for control, control is no longer what’s needed to remedy problematic behaviors.

This little story is a small but powerful reminder of what the highest and best part of you already knows: that compassion makes us protective rather than controlling. The difference is crucial in creating long-term, life-enhancing results.

Jamie Lynne’s full story is included in my Academic Success 101 Online Course

Reaching out …