Dear Difference Maker,

When it comes to hovering, I like to refer to what Mr. Rogers has to say about Limits…

The Helicopter Parent or Teacher

Excerpt from Make a Difference with the Power of Connection

Excessive attention—hovering—is equally destructive and unhealthy for a child’s psychological and emotional development and will guarantee one of two outcomes.

A child who is strong-willed, or has neurological personality wiring that is overt, is more likely to resist and become extremely defiant. A child with a more covert, thoughtful or passive neurological personality may take on a “victim” or “I can’t” behavior.

Excessive attention, repeating directives and constantly checking-in is a put down. It teaches your child to be self-absorbed, instilling the “it’s all about me” world view. Through constant helicopter hovering, trying to know every detail of your child’s life, you are basically saying, “You are incapable of managing your life without me.”

Invasive attention is irritating to a child’s psyche and energetic physiological system. Visualize children growing into competent and capable individuals, and that will benefit them more.

“Hovering like a helicopter” with persistent, pointless and repetitive “Make sure you do this, remember to do that,” aggravates the emotional and psychological health of any child. It will create negative reactions, and lower the child’s self esteem and ability to navigate their world with growing confidence and maturity.

When my son was little, every night at bedtime, I would lie down on the bed with him to read. If there had been a problem that day, this would be the time he would access his feelings and want to talk about it. Largely because of my counseling background, I knew the value of just listening and not fixing.

Rather than tell him what he should do, I simply said, “Let’s both get really quiet and listen to what our inside voice tells us would make this better.” A few minutes later, he would tell me what his inside voice had told him to do to make the situation better. Invariably, what he “heard” was what I “heard” as well.

I knew that the only way my children would ever be safe in the world as they grew up was for them to learn to listen and trust the quiet inside voice, known to most as intuition. But, you say, “What if my children hear a different voice from what I would tell them to do?” Then you simply listen to the child’s reasoning in order to deter mine if it is, in fact, the inside voice or outside voices of society and fear. Intuition, after all, never causes harm to oneself or others.

When my son was eleven, he was headed up the hill on his bicycle to his friend’s house. I told him that because it would be dark soon, I did not want him coming down our hill fast. He was to take it slowly.

After dark, I caught him speeding down the hill and barely making the turn into our yard. When I asked him what was going on for him—that he would not do as I had specifically directed him to do—he said, “My inside voice told me to go fast.”

Was that his intuition or just an excuse? Of course it’s fun to ride down the hill at top speed, but he did that every day, so he understood that this was a special request. I knew he would be coming home after dark and I just felt it would be safer.

Knowing my son, I think he got scared in the dark and felt the need to get home as quickly as he could. Inside voice or fear? Possibly both. Because I was teaching him the importance of listening to his inside voice, I supported his interpretation and didn’t feel it would “teach him a lesson” to take his bicycle privileges away. It paid off in more ways than I can list in this book. All three of our children are world travelers and have the ability to slow themselves down and wait for inner directions and answers.

This is the one thing that gives me ease as a parent when I think of my grown children traveling on the highways and byways of their lives.

And About Consequences!

An educator and parent’s number one job is to foster self-esteem by encouraging age-appropriate dependence while allowing autonomy to develop. Interdependence is a most healthy emotional state which is learned through two-way communication.

Most communication between adults and children is one-way, and that’s why it fails to bring about desired behavior.

If you are having a very difficult time with teen-agers, it’s because you have an attitude, and you are not genuinely extending positive regard or offering a respectful connection.

If you subscribe to the belief that life is going to be a rollercoaster ride when children become teenagers, then that belief is “your attitude,” and you are most definitely programming an expectation that will become a self-fulfilling experience.

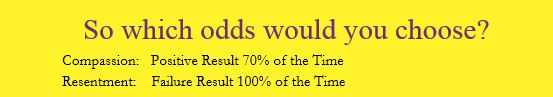

If your attitude is anything but compassionate positive regard, it is interfering with any attempt to communicate. You must modify your attitude by re-labeling your limited beliefs about what your experience will be with teenagers. Start connecting with compassion. It’s not easy for teen-agers to be with adults who consistently launch their negative, limiting “attitudes” at them.

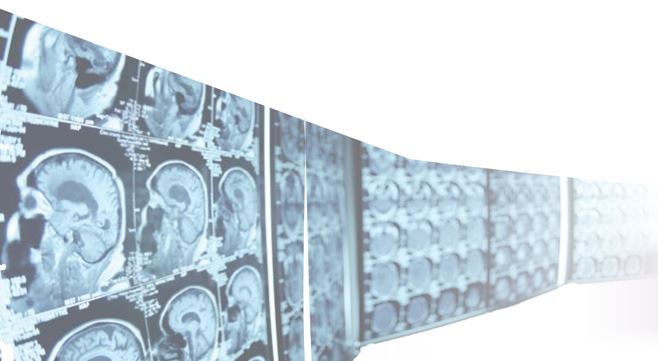

Deborah Yurgelun-Todd is the director of neuropsychology and cognitive neuro-imaging at McLean Hospital in Belmont, MA. Her recent work suggests that teens’ brains actually work differently than adults’ when processing emotional information from external stimuli.

In a recent study of mapping differences between brains of adults and teens, Todd put teenage and adult volunteers into an MRI and monitored how their brains responded to a series of pictures. The results were surprising. When she examined their brain scans, Todd found that the teenagers were using a different part of their brain when viewing the images.

There was an age-dependent or age-related change between the ages of eleven and seventeen, with the most dramatic difference being in the early teen years. One aspect of the scientists’ work has been to look at the frontal part of the brain, which has been known to underlie thought, anticipation, planning and goal-directed behavior. They studied the relationship of this part to the more inferior, or lower part, of the brain, which has been associated with gut responses.

The frontal lobe, the executive region that was studied, is not always functioning fully in teenagers. That would suggest that teenagers aren’t thinking through the consequences of their behaviors. Now this explains so much!

One of the implications of this work is that, in relationship to emotional information, the teenager’s brain may be responding more with gut reaction—impulsive behavior—than with an executive or measured, thoughtful response.

Realize that, if teenagers are not fully developed in thinking through consequences of their behavior, then younger children certainly are not either.

Shaming children into behaving does not teach them to use their judgment, but rather teaches them that they are incompetent, incapable, irresponsible and inept.

This actually induces more of the unproductive behavior, because at” the unwanted behaviors instead of using the language of positive reinforcement, expectation, directives and choices.

Frontal lobe development research now helps us understand how a compassionate response— activating the frontal lobe—to an emotionally upsetting situation soothes problematic behaviors quickly.

This also explains why making desired behavior about the “consequences,” rather than teaching choice-making and skill acquisition, does not teach them a lesson!

Repeatedly threatening harsh consequences will never instill the skill acquisition you want to see children and teenagers growing into.

To read more about Deborah Yurgelun-Todd’s research findings, go to:

www.MakeADifference.com/teenbrain

The teenage brain responds more with gut reaction than with a measured, thoughtful response.

So what do you do with children or teenagers who are out of control, causing harm to themselves or others?

Do this:

• Give ongoing acknowledgment, positive regard and behavior-affirming attention.

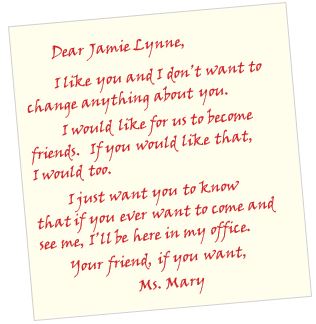

• Make a connection—use two-way communication about behavioral expectations.

• Offer choices, stating best case scenario preferences. Ask the child what he “thinks.”

• Role-play when needed to empower and teach a new skill. Ask the child what she “prefers.”

• Re-label. Suspend your fear and judgment.

• Teach them in very clear terms how they can prove themselves to grow more trust.

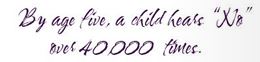

Research indicates that, by the time a child is five years old, he hears the word “No” over 40,000 times and “Yes” only 5,000 times.

Certainly there are times when the answer must be unequivocally “No,” but as the adult, I’ve found those times to be the exceptions not the rule. With our own children, we used the following two phrases to eliminate overusing the word “No.”

In conclusion for today: When we get in touch with our attitudes, beliefs and resistances about any challenging situation we may be dealing with, we, ourselves, will be transformed.

And when we are personally transformed, we set new energy in motion that will instantaneously affect the lives of those whom we touch.

Reaching out …

PS … To Make A Positive Difference by becoming a TurnAround Specialist, check out my Make A Difference with the Power of Acknowledgment UTrain Program and my Academic Success 101 Faculty & Staff and/or Self Paced Online Course for professionals and parents.